Radiation-Immunotherapy Combination Shows Promise in Triple Negative Breast Cancer

May 5, 2023 - Todd AckermanHouston Methodist researchers have discovered a way to turn "cold" tumors "hot" in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), a needed breakthrough to enlist immunotherapy against more cases of the fatal disease.

In a study that provides a proof of concept, a significant percentage of metastatic TNBC patients considered poor candidates for the revolutionary therapy unleashing the immune system responded positively to the treatment when one such drug was combined with radiation and a virus that infects tumor cells.

"This seems to be a way that we can stimulate some triple negative breast cancer tumors to become more responsive to immunotherapy," said Dr. Polly Niravath, a Houston Methodist breast oncologist and study author. "If effective, it could lead to better outcomes for patients with resistant TNBC and may eventually allow for de-escalation of chemotherapy, in the same way that the role of chemo has been rolled back for many HER2+ breast cancers."

The study, published recently in Clinical Cancer Research, marks the first research combining radiation and the two immunotherapies — a checkpoint inhibitor and an oncolytic virus — against triple negative breast cancer, considered the most aggressive and challenging to treat of breast cancers.

Much recent research into TNBC treatment has investigated the use of checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy, a mix that's extended the lives of some metastatic patients. Those responders had so-called hot tumors, which are often characterized by molecules on their surface easily recognized by immune cells. The mix has been ineffective in so-called cold tumors, which are often characterized by cells able to suppress the immune response.

"Like poking a beehive"

Dr. Niravath said adding radiation and an oncolytic virus to a checkpoint inhibitor is "like poking a beehive," waking the tumor up and inflaming it. The idea, said Dr. Niravath, is to make the tumor a "little bit angry, more immuno-reactive."

Houston Methodist's trial, a Phase II known as STOMP, found a clinical benefit in more than 20% of participants, all of whom had low or negative PD-L1, the protein that checkpoint inhibitors act on to activate an immune response. Tumors with such low or negative PD-L1 are considered cold and typically not treated with checkpoint inhibitors.

Study participants also had previously relapsed or proved resistant to standard-of-care therapy. In some cases, the cancer had traveled to the liver.

Historically, triple negative breast cancer, so named because it doesn't have any of the three targetable receptors commonly found in other breast cancers, has been treated, with limited success, with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. If the tumor is unresectable or becomes metastatic, the median overall survival is eight to 13 months.

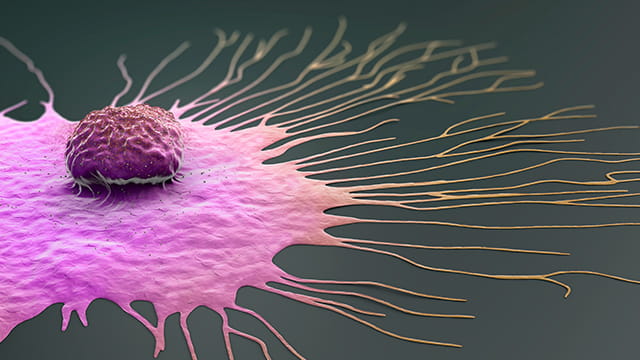

The current challenge is figuring out how to tap immunotherapy's potential for TNBC, which accounts for between 10% and 15% of all breast cancers and lacks the targeted treatment options of other breast cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors remove a brake that reins in the immune system, but if there are few circulating T-cells at the site of the tumor, ready to attack, the drugs have little effect.

Radiation's mysterious abscopal effect

That's where the oncolytic virus comes in. It replicates in a cancer cell until the cell bursts, releasing antigens that help the immune system recognize the cancer. Radiation, besides killing cancer cells, provokes a similar immune response.

Dr. Niravath also noted radiation's abscopal effect, the not-well-understood ability to induce an antitumor response throughout the body, specifically in sites that were not targeted. Even though Houston Methodist researchers radiated only one metastatic site, she noted, the therapy seemed to have a positive effect on the immune system in other areas.

The trial consisted of 28 patients, all of whom received the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab; a herpes oncolytic virus injected directly into the tumor at its most accessible site; and radiation at the site of the injection.

Six of the patients had a clinical benefit — two a complete response, one a partial response and three stable disease. Patients with such a benefit had durable responses, with a median duration of treatment of 9.6 months and median overall survival of 14.7 months, which was more than twofold the survival time in the trial's total population.

The therapy was well-tolerated, study authors wrote in the paper.

Getting the therapy to more patients

The authors also wrote that although the study did not meet statistical significance, the durable responses in such heavily pretreated patients, with low PD-L1 and liver metastases in some cases, suggests that checkpoint inhibitors are enhanced by radiation and oncolytic viral therapy. Dr. Jenny Chang, director of the Houston Methodist Dr. Mary and Ron Neal Cancer Center, led the study.

If the combination is shown to be effective in larger trials, Dr. Niravath said the hope is to move it into earlier disease stages, where responses tend to be better. Eventually, she said, the hope is to offer the therapy to more TNBC patients generally, regardless of whether their tumor is very immune-active.

The Houston Methodist research team is currently enrolling patients, not metastatic, in a trial (INTEGRAL) investigating the same concept but using a different combination — this one a mix of immunotherapy and chemotherapy. The trial design calls for patients who don't respond to the first phase of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and pembrolizumab to delay the planned second phase and instead get interleukin 12, a potent, proinflammatory cytokine that inflames tumors in much the same manner as an oncolytic virus. Such patients will then receive the trial's second neoadjuvant chemo-pembro phase.

Early results have looked promising, said Dr. Niravath.

"With these immunotherapy trials, we're seeing that there's a small proportion of TNBC patients that get a durable extended benefit from immunotherapy," said Dr. Niravath. "Of course, the million-dollar question is how do we identify the patients who we can give a significant benefit and keep in remission for years? That's very rare in this type of cancer, but it looks like we're seeing some signals that it is possible."