Heart Valve Replacement With Dr. Michael Reardon: Is TAVI Better Than Surgery?

May 10, 2021 - Todd AckermanA minimally invasive procedure to replace a failing heart valve is exploding in popularity, but a leading Houston Methodist practitioner warns that not everyone is a good candidate and calls on heart-care teams to make sure patients understand all the considerations.

Dr. Michael Reardon, principal investigator of some of the studies that led to the FDA's approval of transcatheter aortic valve implantation — TAVI, for short — for high-risk, intermediate-risk and, most recently, low-risk patients, will speak at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in May about how surgery is nevertheless sometimes still the best intervention.

"Younger patients are going to need to make complicated decisions about which procedure is best for them based on the lifetime management of their condition," says Dr. Reardon, a cardiothoracic surgeon. "There are good reasons that doctors will recommend that TAVI isn't appropriate for some of them."

Dr. Reardon says doctors will need to take into account the fact that many younger patients likely will need more than one aortic valve intervention, and that the TAVI studies didn't enroll some groups of patients who may not respond as well.

The talk comes just months after the ACC and American Heart Association issued new guidelines that recommend:

- TAVI for patients older than 80 and with a life expectancy of less than 10 years

- Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for patients younger than 65 and with a life expectancy of more than 20 years

- A joint decision by the doctor and patients age 65 to 80 based on patient physiology, anatomy and personal wishes

About transcatheter aortic valve implantation

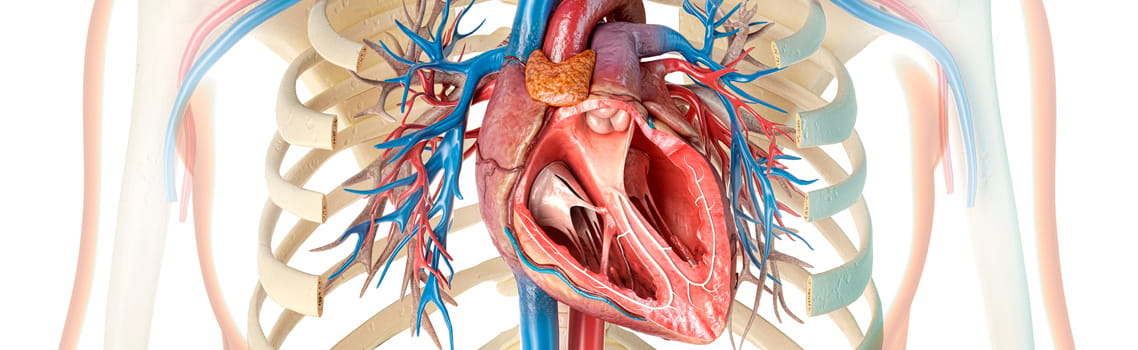

TAVI treats patients with aortic stenosis, a condition, caused by an accumulation of calcium, that narrows the aortic valve and makes it more difficult for the blood to leave the heart and travel to the rest of the body. Former First Lady Barbara Bush drew attention to the condition more than a decade ago when she was treated for it at Houston Methodist.

The condition, fatal if not treated, historically required open-heart surgery, which involves cracking the ribs apart and stopping the heart to insert an artificial valve. With TAVI, the only incision is a small hole in the groin where a catheter is inserted.

In the procedure, a wire is inserted into the groin artery and passed through the patient's vascular system into the heart. There, the valve is expanded, pushing the patient's old valve out of the way and functioning as a new valve. This relieves the obstruction, circulating blood through the body better.

The procedure's appeal is obvious. Recovery takes days, not the months that typically follow open-heart surgery. Patients, awake throughout the procedure, barely feel a thing.

The result: TAVI has become patients' most requested aortic valve repair intervention. Volumes have increased every year since initial U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for inoperable or extreme risk patients in 2011. Following the FDA's 2019 approval for low surgical risk patients, TAVI procedures exceeded all forms of SAVR for the first time — 72,991 to 57,626.

Houston Methodist's TAVI team has performed more than 2,000 of those implantations, among the most in the nation. Dr. Reardon, a vocal proponent of TAVI, says that patients under 65 come into his clinic every day asking for the minimally invasive procedure rather than surgery.

TAVI versus surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)

In many patients, aortic valve intervention decisions will require careful evaluation.

"As the age of patients wanting TAVI continues to drop, we're going to see many who'll need more than one procedure in their lifetime," says Dr. Reardon. "How do we do those series of procedures? Do we do a SAVR, then a TAVI, then another TAVI? A TAVI, then a SAVR, then another TAVI? There are lots of ways to put together a treatment plan."

Dr. Reardon tells of Houston Methodist patients who did better with surgery: a 74-year-old woman who didn't improve after her Louisiana doctor replaced her worn-out surgical valve with a too small TAVI valve; a 74-year-old man who wanted TAVI but wasn't a great candidate because of a calcium pattern in his bicuspid aortic valve.

Bicuspid vales, those with only two flaps instead of three, are among the categories Dr. Reardon says may fare better with surgery. Others include significant coronary disease, poor anatomy, an age younger than 65 and a need for concomitant procedures such as Mitral valve repair or atrial fibrillation ablation.

None of those groups were well represented in the studies — whose protocols excluded the riskiest of patients — that led to the approval of TAVI. Dr, Reardon refers to the "knowledge gaps" that have thus resulted in calculations of who'll benefit from TAVI.

Dr. Reardon says the key is a well functioning heart team, knowledgeable about both surgical and transcatheter interventions, to determine what's in a patient's best interest and to help him or her decide which to have. He cites Houston Methodist's team as a model of such teamwork, never battling over which specialty should perform the procedure.

"In the short term, in the right patients, TAVI beats the pants off surgery," says Dr. Reardon. "But we still don't know how TAVI will hold up 10 to 20 years out.

"What we do know is that TAVI is here to stay, moving into younger and lower-risk patients who are going to be more active and have a longer lifespan. That'll make decisions more dependent on heart care teams that work well together and understand the knowledge gaps that still remain."